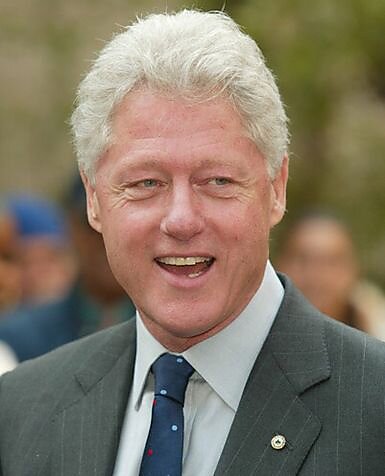

Twenty-five years ago, President Clinton’s midnight pardon of fugitive financier Marc Rich triggered universal outrage. Today, public reaction to an array of similar presidential pardons is often silence or a shrug: The uproar over Rich’s pardon in 2001 contrasts sharply with the numbness and resignation that President Trump’s pardons produce today. It is tempting to explain the change by invoking something like national amnesia or national denial. But it is more precise to say that our moral and political standards for the exercise of the presidential pardon have collapsed. The case of Marc Rich illuminates the standards that we should hold our presidents to; Trump’s behavior illuminates our failure to do so.

Marc Rich was an extraordinarily wealthy and successful commodities trader. He was also, according to the US Department of Justice, an extraordinarily dangerous white-collar criminal—on the day he was pardoned, he was on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. Some years before, Rich was the subject of a 65-count indictment: It alleged systematic tax fraud through sham transactions that resulted in the evasion of more than $48 million in tax liability, as well as repeated violations of the US embargo against Iran through illegal oil trades. Unlike most recipients of presidential pardons, Rich had neither served time behind bars nor expressed remorse; instead, after he was indicted for the largest tax fraud in American history, he fled the United States, sequestering himself in his luxe Spain and Switzerland villas for the next three decades amid his collection of Renoirs, Monets, and Picassos. His ex-wife, Denise, was a major Democratic Party donor: Before Marc’s pardon, Denise had given over a million dollars to Democratic campaigns and the Clinton family’s personal causes—as well as $450,000 to the Clinton Library.

The procedure for Marc Rich’s pardon was unusual: The standard route to a pardon incorporates extensive vetting by multiple lawyers in the Department of Justice’s Office of the Pardon Attorney, but President Clinton bypassed this traditional path. His circumvention of normal procedures for pardon deliberations created speed, secrecy, and insulation from almost everyone else in the Clinton administration. The formal mechanisms of the Office of the Pardon Attorney are meant to wall off the White House from anything like quid pro quo transactions; conversely, the informal decisionmaking that Clinton resorted to when he pardoned Rich on the very last day of his administration invited suspicions of corruption.

Like every president, Clinton had a retinue of political defenders—but they couldn’t defend the Rich pardon. Rep. Barney Frank (D‑MA) said: “It was a real betrayal by Bill Clinton.… It was contemptuous.” Sen. Paul Wellstone (D‑MN) said: “It puts back into sharp focus all the questions about values and ethics in relation to the Clinton administration.” Sen. Patrick Leahy (D‑VT) called it “terrible,” “inexcusable,” and “outrageous.” Former President Jimmy Carter said, “I don’t think there is any doubt that some of the factors in his pardon were attributable to his large gifts. In my opinion, that was disgraceful.”

As one might expect, Republicans’ criticisms were somewhat less nuanced. Mickey Cantor, a long-time confidante of President Clinton, provided a perceptive account of the problems of the Rich pardon in an interview:

The first question is, why pardon anyone at all if the Justice Department hasn’t given you a recommendation? … Number two, even if you decide you’re going to pardon people, why would you allow any outsider to have access to you in discussing it? Three, even if you allowed everything to happen, if your entire staff says no, wouldn’t it occur to you that it’s a problem? It is the single most inexplicable, devastating thing he did.

Ten years after the Rich pardon, journalist Dafna Linzer described its aftermath. Her article began: “Few pardons have had a more lasting effect than President Clinton’s 11th-hour decision to forgive Marc Rich.” That pardon, she wrote, “changed the political landscape, making presidents much more cautious about using a Constitutional power that is without limit.” She explained that, after the Rich pardon, “President George W. Bush decided to rely more on recommendations from the career officials in the Justice Department’s Office of the Pardon Attorney. Bush hoped that this would discourage the politically well-connected from directly lobbying the White House.” Her account, published two years into the Obama administration, explained that George W. Bush granted the fewest pardons of any modern two-term president: 189. She then noted that at the time, Obama was “on pace to be even more parsimonious.” Of course, hindsight is twenty-twenty, but the view from 2026 shows that Linzer’s 2011 perspective was too optimistic: Her hope that we would learn from experience has proven false.

Tomorrow, I will summarize the pardons that President Trump issued during the first year of his second term. Here’s the short version: The Rich pardon was a raindrop, Trump’s pardons are a hailstorm.